1. Buy the program. Imagine if you had bought one work from every show at the Daniel Weinberg Gallery in Los Angeles during the late 1980s. You would have ended up with a Robert Gober (and a sink, no less), a John Chamberlain, an Eric Fischl, and a Robert Ryman. Ingratiate yourself with a dealer who has picked winners in past eras, such as Paula Cooper, or more recently David Zwirner, James Cohan, Adam Baumgold and Zach Feuer, and watch your art portfolio soar.

2. Sacrifice your pawn (to get to the queen). Often, to make the above strategy viable, a collector finds him- or herself having to buy a work or two by a gallery’s less celebrated artists. Many years ago, some believed that a good way to approach the Mary Boone Gallery to obtain a work by Fischl or Schnabel was to offer to buy a Gary Stephen or a Michael McClard. Even the great Leo Castelli smiled upon those seeking a Lichtenstein, Johns or Stella if they asked to buy a Cletus Boyer, Mia Westerlund Roosen or even a Keith Sonnier.

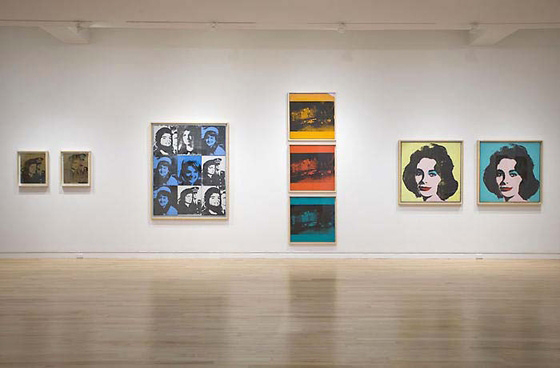

3. Buy from an artist’s estate. Be it Sam Francis or Andy Warhol, lucky are the collectors and dealers who can get close to an artist’s estate, and be able to cherry pick from the trove of paintings the artist has left behind. Estates often sell work below market for several reasons, including to avoid speculation. Their strategy is to place pictures with bona fide collectors who will hold onto the work rather than ship it off to auction. If you are lucky enough to be able to acquire pictures from an estate, handle your opportunity responsibly -- there are no second chances.

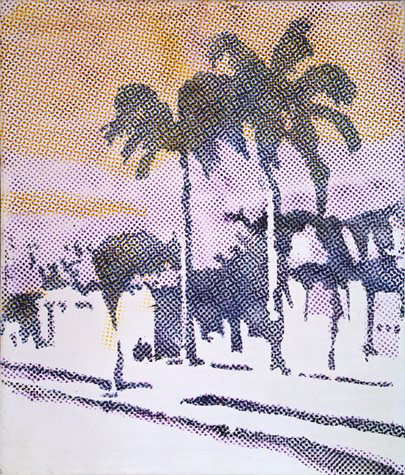

4. Buy new release prints. Even though prints are less likely to jump in value than paintings, they do offer opportunities for appreciation. And when it comes to prints it’s all about the publisher. Having a subscription to ULAE, or to a lesser extent to Gemini and Crown Point Press, insures you of the opportunity of buying prints at their IPO (initial public offering) price. Once the edition sells out, the publisher automatically raises the price.

5. Buy items that pass at auction. Risky business but highly lucrative when it works. When an artwork fails to make its reserve, anyone can approach the auction house with an offer to buy it after the sale. On the negative side, the whole art world is aware the thing didn’t sell and hangs the scarlet letter "B" (for Burned) on it, claiming it was either inferior, grossly over-estimated, had dubious title or some other defect. Think independently. If you decide that it’s a quality work, go for it and make the auction house a lowball offer. If the firm accepts, not only will you have gotten a bargain, but no one will know what you paid for it. When you go to sell someday, that will prove extremely beneficial.

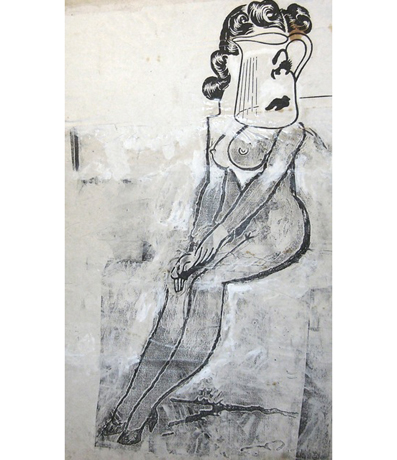

6. Buy directly from an artist’s studio. Some artists are extremely loyal to their dealers. Then there are those. . . . If you choose to work with an artist who sells direct, be aware that most of them like to be paid in cash. You’d be shocked at some of the big names who will bend the rules to pick up spending money for vacations, greens fees and fancy restaurants. Remember, I’m not advocating that you do anything illegal. Just be cool about it so neither the artist or his dealer are embarrassed. Under certain circumstances, some dealers are willing to look the other way when an artist makes deals on the side, such as Andy Warhol’s arrangement with Leo Castelli.

7. Buy pre-retrospective. If you discover that a major art world figure is about to receive a full-dress retrospective, it’s time to spring into action. There’s nothing like anticipation of a major show to put an individual artist’s work in play -- the price of a work of art always goes up on the come. If you already own a painting by the artist about to be canonized, do everything in your power to lend your work to that show -- all the better to have your painting documented, which increases its value.

8. Buy an artist who is switching galleries. Artists are human. When an opportunity to exhibit at a more important gallery comes their way, chances are they’re going to take it. Try and buy a painting before the changeover becomes official. In one recent example, Robert Bechtle jettisoned a 30-year relationship with O.K. Harris for greener pastures at Gladstone Gallery. By exhibiting at a gallery with a stronger reputation, Bechtle’s work was seen in a fresh context, which helped his prestige, to say nothing of his prices.

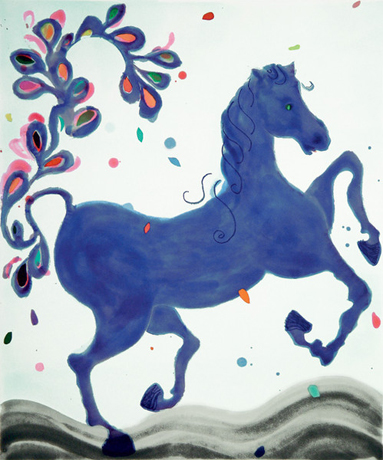

9. Piggyback a purchase on a museum trustee. If you want to make a sharp investment, just find out which artist your local museum’s trustees are currently acquiring for their personal collections. You will find that even though it’s a conflict of interest, a "value-increasing" show of that particular painter, at that particular museum, is rarely far behind. Years ago, the San Francisco Museum of Modern Art held a large survey of Sigmar Polke’s recent work. While reading the wall labels, I noticed that a good proportion of the show was owned by members of the board. What a surprise.