Imagine making it to the top of the heap in your chosen profession. Think about all of the blood, sweat and tears that went into that arduous climb to the peak. Ponder all of the setbacks that you experienced as you struggled to learn from your mistakes and improve your craft. Now contemplate what it would have been like to have trained as a painter at Yale, but become an author who went on to write a book that sold over 160,000 hardcover copies (The Martini). From there you went on to other literary successes, but at some point decided you wanted a bigger challenge. You wanted to paint again. Welcome to the world of Barnaby Conrad III.

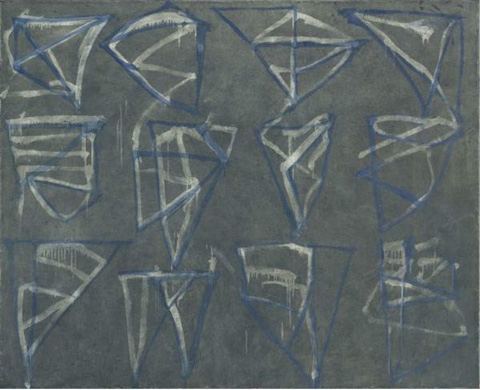

With the opening of his first solo show in New York, titled “The Aquatic Life,” on the Upper East Side at M. Sutherland Fine Arts, Conrad’s creative life has come full circle. The exhibition itself is a provocative display of slightly surrealist imagery that depicts the marine life Conrad observed this past summer at his home in Virginia, along the Eastern Shore. Conrad turned his attention to the physical beauty of the area, finding inspiration in the region’s water world, especially its blue crabs. In reality, these crustaceans and their pleasing forms provide an excuse for Conrad to explore formal painting concerns -- namely color, structure and psychological content. But they are also metaphors for his profound respect of the great outdoors and all of its natural wonders.

There’s one painting in particular that hints strongly at Conrad’s potential as a painter. Blue Crabs, Male and Female #2 radiates energy, as linear sonic waves seem to pulsate from the two crabs. Are they mating? Trying to escape a fisherman’s net? Or are they simply caught up in the maelstrom of their watery existence?

As I continued to walk through the show, I also come upon a number of leaping trout, which focused on the painter’s love of fly fishing, and called to mind past travel adventures that he still savors (see his book Ghost Hunting in Montana).

But while I was looking at the artworks, I found myself asking a greater question. Namely, how does someone who found success in one creative field try his hand in an equally competitive arena, while setting the bar high? In other words, how do you go from a career as a writer, with plenty of accolades, sales, and big-time publishers, to being taken seriously as a painter in the competitive New York art world?

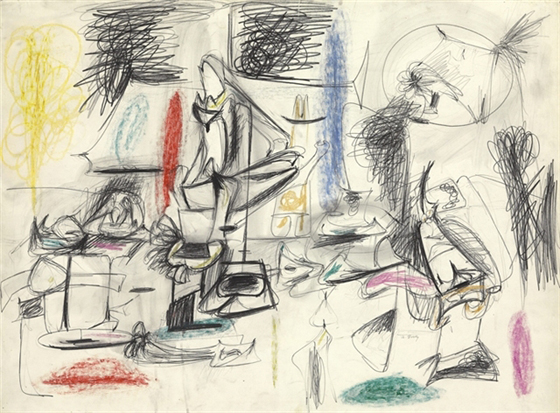

Being married to an art dealer certainly helps -- Conrad wisely wed the lovely Martha Sutherland several years ago. But a more serious answer may be found in considering the lives of other creative people who succeeded at what Conrad is trying to accomplish. The first to come to mind is Julian Schnabel. As we all know, he emerged as an art world superstar during the 1980s, becoming as famous for his plate-encrusted paintings as for his statements of braggadocio, such as the classic, “I’m the closest you’ll come to Picasso in this lifetime.” While Schnabel’s paintings, even at their best, hardly fulfilled that boast, there was something to his work.

Then Schnabel got involved with filmmaking, directing the surprisingly good movie Basquiat. While the story contained a number of inaccuracies, such as Schnabel leading the viewer to believe that he was tight in real life with Jean-Michel Basquiat, the movie showed a promising start as a director. At the time of Basquiat’s release, Schnabel took a lot of flack for crossing-over into film. My suspicion is Conrad may face the same skeptical attitude, and have to defend his decision to paint. But then Schnabel went on to direct Before Night Falls, which garnered all sorts of international acclaim and awards. Suddenly, critics were not only fawning over him as a filmmaker, but they were also praising his paintings. Julian Schnabel was finally seen as a true artist. It wouldn’t surprise me that by the time of Conrad’s second show -- Modernism Gallery in San Francisco is giving serious thought to exhibiting his next body of work -- that the art world begins to view him with the same rose-colored glasses as the literary scene.

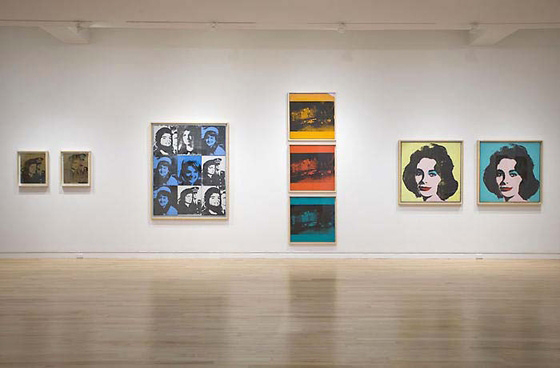

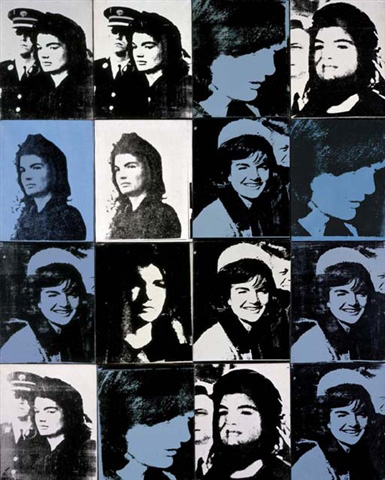

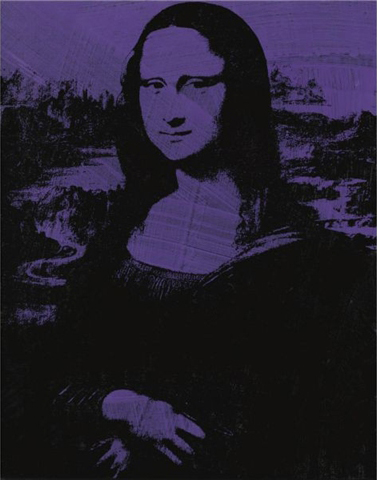

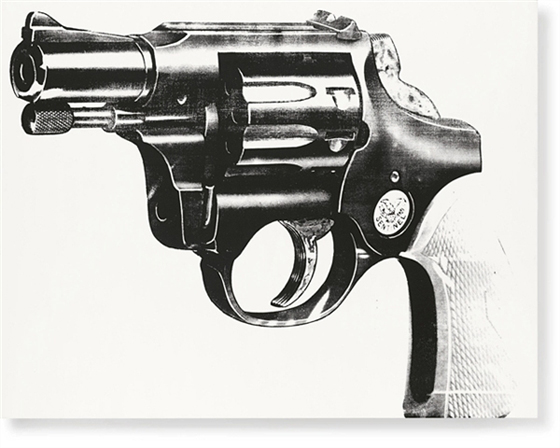

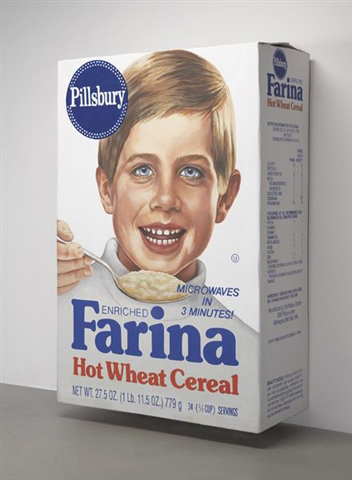

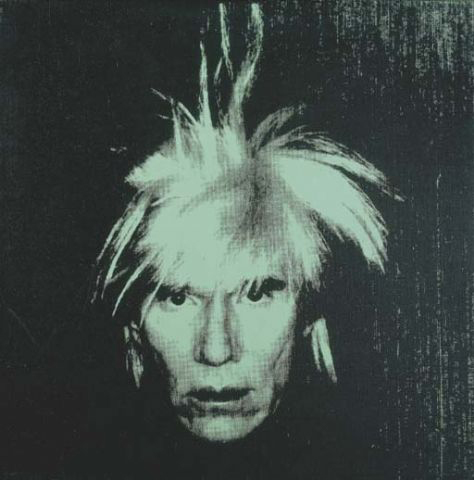

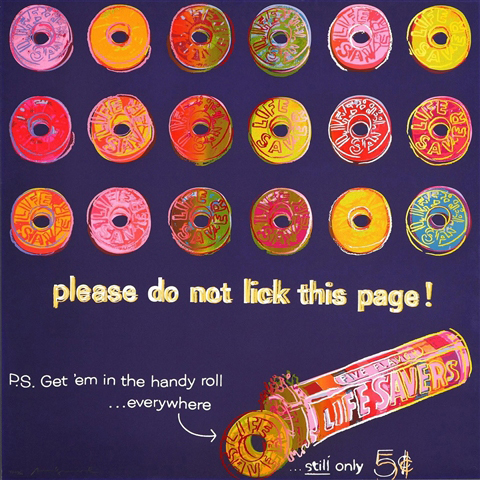

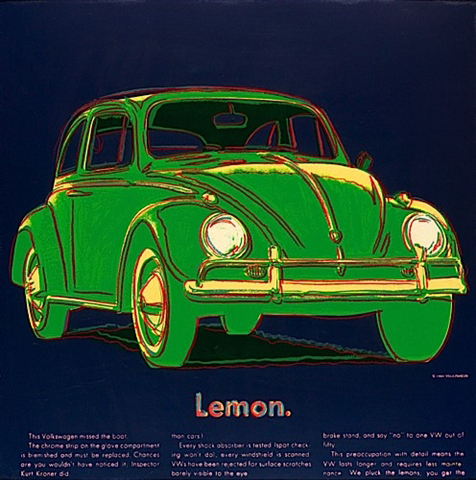

Another example of a crossover artist that springs to mind is Peter Coyote. Long known as an actor, and for narrating various Ken Burns documentaries, Coyote found himself writing a memoir (in 1998) called Sleeping Where I Fall. The book was terrific. The former Peter Cohen came across as an original voice, spinning yarns about his ‘60s counterculture lifestyle in San Francisco. The success of the book also led to a greater appreciation of Coyote’s acting skills. Once again, I see a correlation with Conrad’s paintings leading to increased respect for his writing, including his first serious stab at fiction, The Bachelor’s Progress, a novel that is currently being shopped. And then of course, there’s Andy Warhol, the ultimate example of a great artist who parlayed his accomplishments as a painter into virtually every creative endeavor that he chose: film (Chelsea Girls, etc.), music (the Velvet Underground) and publishing (Interview). While it’s obviously a stretch to suggest that Conrad (or anyone for that matter) can ultimately match what Warhol achieved, it does illuminate the wisdom of risking his standing as an acclaimed author to swim in the deep end and follow his heart by exhibiting his paintings.

RICHARD POLSKY is the author of the recently released book on the art world, I Sold Andy Warhol (too soon).